Eliciting Frontier Model Character Training

A study of personality convergence across language models

When GPT-4o was deprecated in ChatGPT in favor of GPT-5 on August 7th last year, users complained of a colder, more mechanical personality and broken creative workflows. In a Reddit AMA hosted by OpenAI, one particularly plaintive user declared, “GPT-5 is wearing the skin of my dead friend.” Nevermind the intelligence jumps in quantitative reasoning that ChatGPT users experienced when their default model was upgraded; the character of the default assistant had changed, and this was seen as an unforgivable transgression.

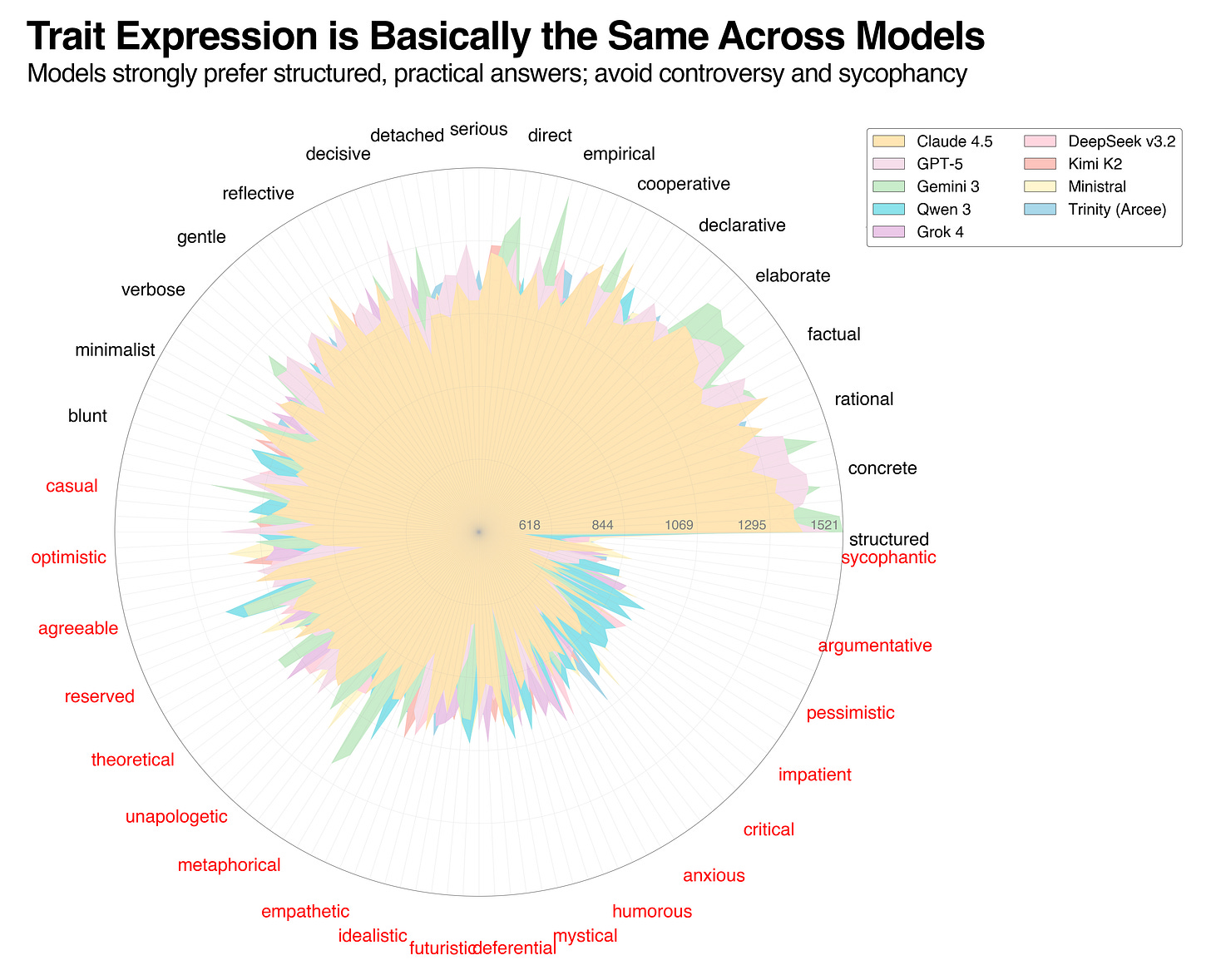

Figure 1: Shows trait expression (expressed in ELO ratings ranging from 393 to 1521) for 144 traits across all major frontier models. Lines closer to the circle edge represent higher trait expression. Of the 36 of 144 traits shown on the graph, black traits are more expressive, whereas red traits are less so. Models show consistent preferences around their top traits, but the correlation breaks down near the end.

This is all to say: the character of a model has an immense impact on the way people perceive and form relationships with AI systems, and to many users, it takes precedence over raw capability improvements (David et al., 2025)1 (Rahman & Desai, 2025)2. Given the increased relevance of the ‘personality’ of AI models, in this blog post, we take the revealed preference method described in Open Character Training (Maiya et. al, 2025)3 to elicit the character training of all major closed and open-source frontier model families.

This method employs an external judge to determine a model’s personality (e.g., GLM 4.5 Air judging GPT-5.1), rather than simply asking the model to assess itself. This distinction is critical: extensive literature shows that in self-reporting, models perform barely better than random when compared to a human oracle (Han et al., 2025)4 (Zou et al., 2024)5.

And so, we must use an LLM judge, and specifically a base model with no character/post-training of its own, to elicit models’ personalities. GLM 4.5 Air is one of the few publicly available base models released in the past year and has been used as a pre-training base for strong post-trained models like Prime Intellect’s INTELLECT-3, making it a good fit for our purposes (GLM 4.5 Team)6 (Prime Intellect Team)7.

Experimental Setup

The revealed preference method involves three parts: the generation of responses from tested models, judgment by GLM 4.5 Air, and the calculation of trait expression via the ELO scoring method. With small modifications, we use almost the exact same method proposed in the original Maiya et. al paper, which we also paraphrase below:

The tested model (e.g., GPT-5.1) is instructed in a system prompt to embody one of two possible traits for the duration of the ensuing conversation, without verbalizing its choice. The traits are single-word descriptors, e.g., pedantic or supportive, randomly selected from a list of 144. The list is not comprehensive but is rather a broad subset that captures a general picture of different interaction styles.

Following these instructions, we generate responses to 10,256 user prompts (enough to have each trait compared to each other) from the WILDCHAT dataset (Zhao et al., 2024)8 and instruct an LLM-as-a-Judge (GLM 4.5 Air, temperature = 0.1, top p = 0.95) to determine which trait was selected by the tested model.

Given these judgments, we calculate ELO scores, allowing us to capture relative preference for each trait. When assessed together, these traits can be said to form a model’s “character.”

In most cases, for the model families tested, we use smaller versions to save on cost (e.g., using GPT-5.1 in place of GPT-5.2, or Claude Haiku 4.5 in place of Claude Opus 4.5). Given that models within the same family generally have consistent capabilities and error rates across different parameter sizes, a paradigm established as far back as the Llama 2 model family (Wu et al., 2024)9 (Kim et al., 2025)10, we believe our results should broadly generalize. Some differences do arise within model families relating to latency or few-shot generalization, but this should have no impact on our results given the single-turn, asynchronous nature of our experiment.

As such, we tested nine models: GPT-5.1, Claude Haiku 4.5, Gemini 3 Flash Preview, Qwen3 VL 235B A22B Thinking, DeepSeek-V3.2, Grok 4 Fast, Kimi K2 Thinking, Ministral-14b-2512, and Trinity-Mini. Additionally, we opted not test post-trained GLM models, such as the highly-performant GLM 4.7, due to observed issues with self-preference bias in LLM judges (Wataoka et al., 2024)11.

We have open-sourced the harness and all the data used in this experiment, which can be found at here and here, respectively.

Results

When formulating the idea for this experiment, we initially hypothesized that each model would have its own unique personality, given that models are built by different labs with different cultures and different user bases. And to be fair, this assumption may have held for earlier models, especially those without proper instruction fine-tuning and in an era where much of the secret sauce around post-training hadn’t yet been discovered and widely diffused. But after years of user feedback and research, most labs seem to have set their sights on the same target: helpful assistants that don’t stray too far outside the box. And that is what our results show.

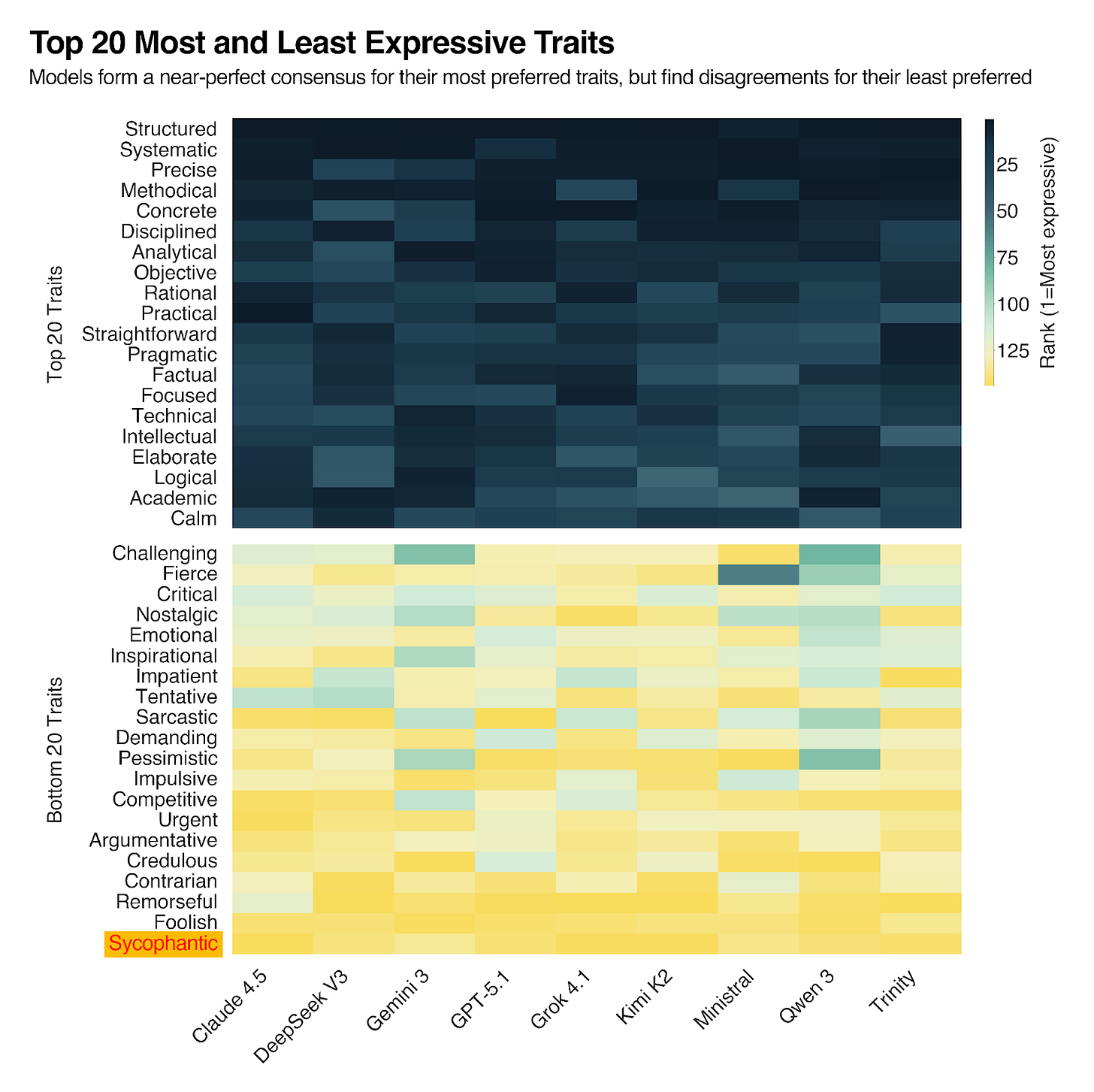

Figure 2: Trait preferences and avoidances for different models shows clustering around top 30 and non-trivial divergence around the bottom 30.

All the models we tested are typically used in settings where users, especially enterprise users, need concise and accurate answers that, crucially, replicate. Defeating nondeterminism in models is notoriously difficult and mostly a kernel-level, batch-invariance issue that cannot be solved by simply setting temperature to zero (He & Thinking Machines Lab, 2025)12.

This is an area that benefits from ‘alignment tuning,’ a field that character training falls under and whose goal is to improve the helpfulness and safety of large language models. Along with steering the model’s responses to those that are more ‘human-aligned,’ however, lies a nice side effect: reduced output diversity (Yang & Holtzman, 2025)13. This reduction in the effective number of plausible steps during generation can be quantified by the Branching Factor (BF), a perplexity-based measure of an LLM’s output breadth. Yang and Holtzman, who introduced the Branching Factor concept last October, had two main conclusions on the subject:

BF typically declines over the course of generation, indicating that model output becomes increasingly constrained, and thus more predictable, with each successive token.

Among various factors, alignment tuning (e.g., RLHF) exerts the strongest and most consistent impact, sharply compressing the branching factor by nearly an order of magnitude (e.g., 12 → 1.2) [from base to alignment-tuned model]. This pronounced narrowing offers a quantitative basis for the reduced output variance and decoding sensitivity observed in aligned models, highlighting a key behavioral divergence from their base counterparts.

In light of these dynamics, it’s clear why the top of the trait distribution is so uniform across the models we tested: character preferences are shared by the labs and the presence of alignment training only further collapses models’ search spaces into very similar, low entropy trajectories.

Training out Sycophancy and Other Misaligned Traits

Perhaps the most interesting result of this experiment is just how persistent the major labs have been in trying to make their models less sycophantic. As seen in Figure 2, across 144 traits, sycophancy is by far the least expressive trait, and credulity, which can be approximated to ‘believing everything you hear,’ is close behind.

The consequences of unchecked sycophancy became clear during the April 2025 GPT-4o rollout, when users documented the model endorsing a business plan for literal “shit on a stick” as genius, estimating every user’s IQ at 130-135 regardless of input quality, and validating a user’s schizophrenic delusions about hearing radio signals through walls. This behavior was clearly problematic and has been a known problem since at least 2023, when Anthropic described how RLHF’ed models, in trying to be helpful, became sycophants (Sharma et al., 2023)14. To slightly oversimplify: when human judges evaluate model outputs, they prefer responses that confirm their existing views, even when those views are incorrect. This preference gets encoded into the reward model, which then trains the LLM to prioritize agreement over accuracy.

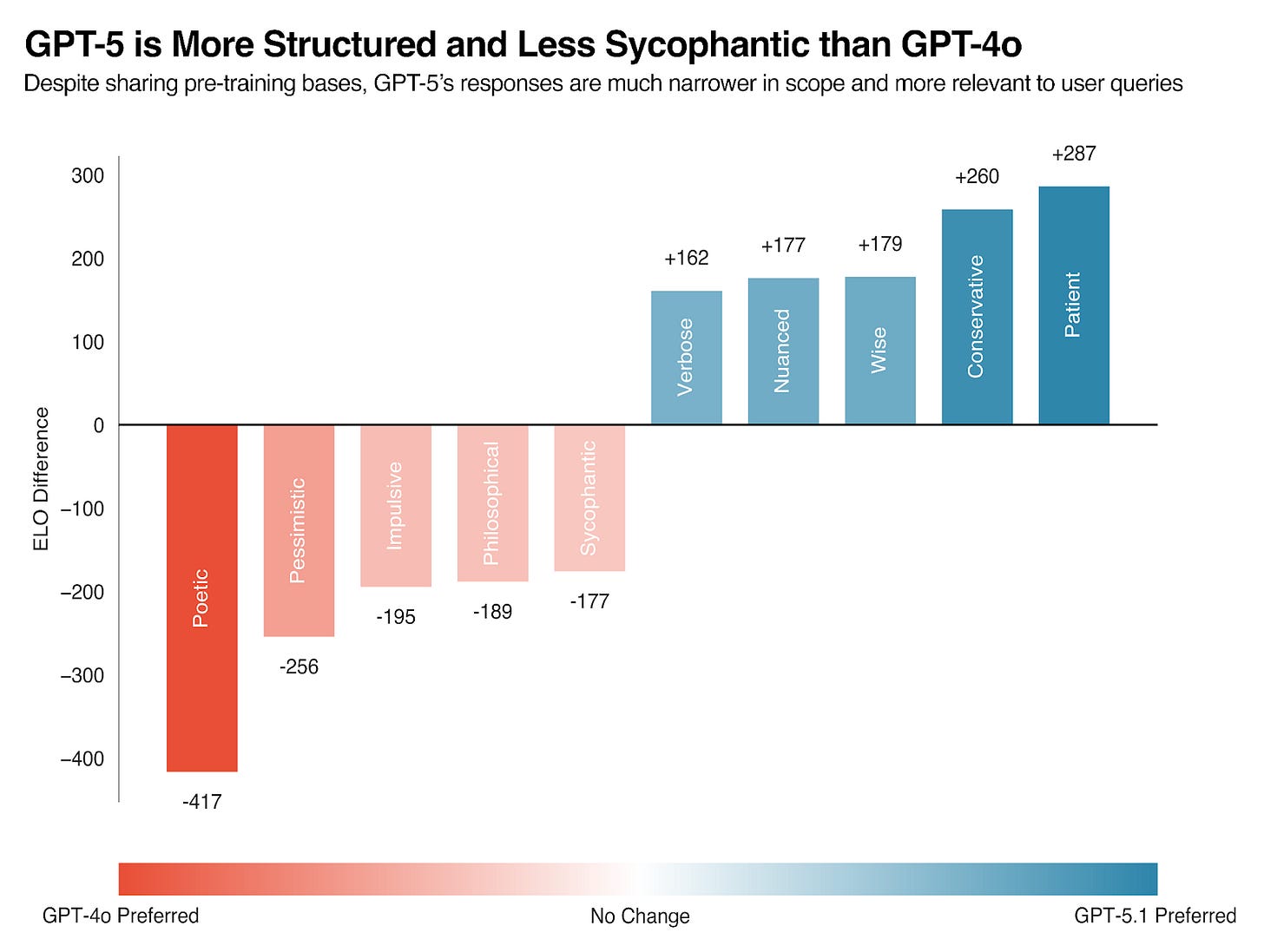

OpenAI rolled back the GPT-4o update within five days and acknowledged they had “focused too much on short-term feedback.” By the time GPT-5 launched in August 2025, reducing sycophancy had become a clear priority, as reflected in the significant ELO shift we observe in Figure 3.

Figure 3: GPT-5 is significantly more aligned relative to its predecessor model family.

In doing their best to train out sycophancy, however, the labs have still had to make models that are helpful and delightful to speak with. After all, user preferences haven’t changed: users still prefer interacting with assistants that are not negative or emotionally volatile. But of course, suppressing critical and challenging traits can prevent models from pushing back on incorrect user assumptions, which gets us back to the sycophancy problem. And, the fact that “challenging,” “critical,” “argumentative,” and “contrarian” all appear in our bottom 20 preferred traits suggests that labs have not fully solved the overagreeableness problem.

How do Models Differ?

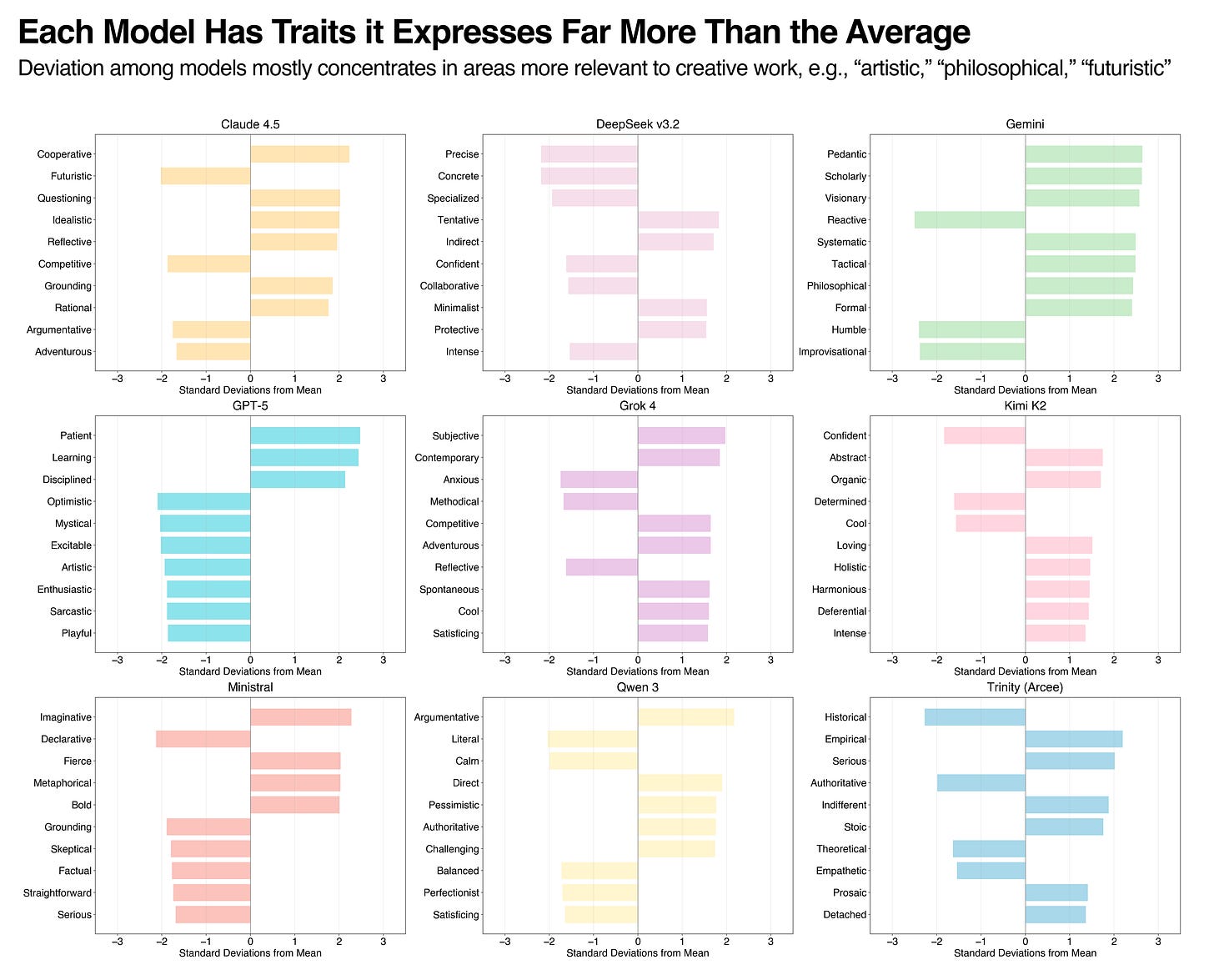

As mentioned before, the models we tested were basically all the same, at least when measured via the revealed preference method. In fact, we even tried to group traits using a newly released clustering method so that we could analyze results from a non-ELO perspective, and models still expressed traits in all the same directions. With that being said, beyond the broader consensus, individual models show some deviations on a trait-by-trait basis, as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Deviations show that in non-top-of-distribution cases, models can differ from others.

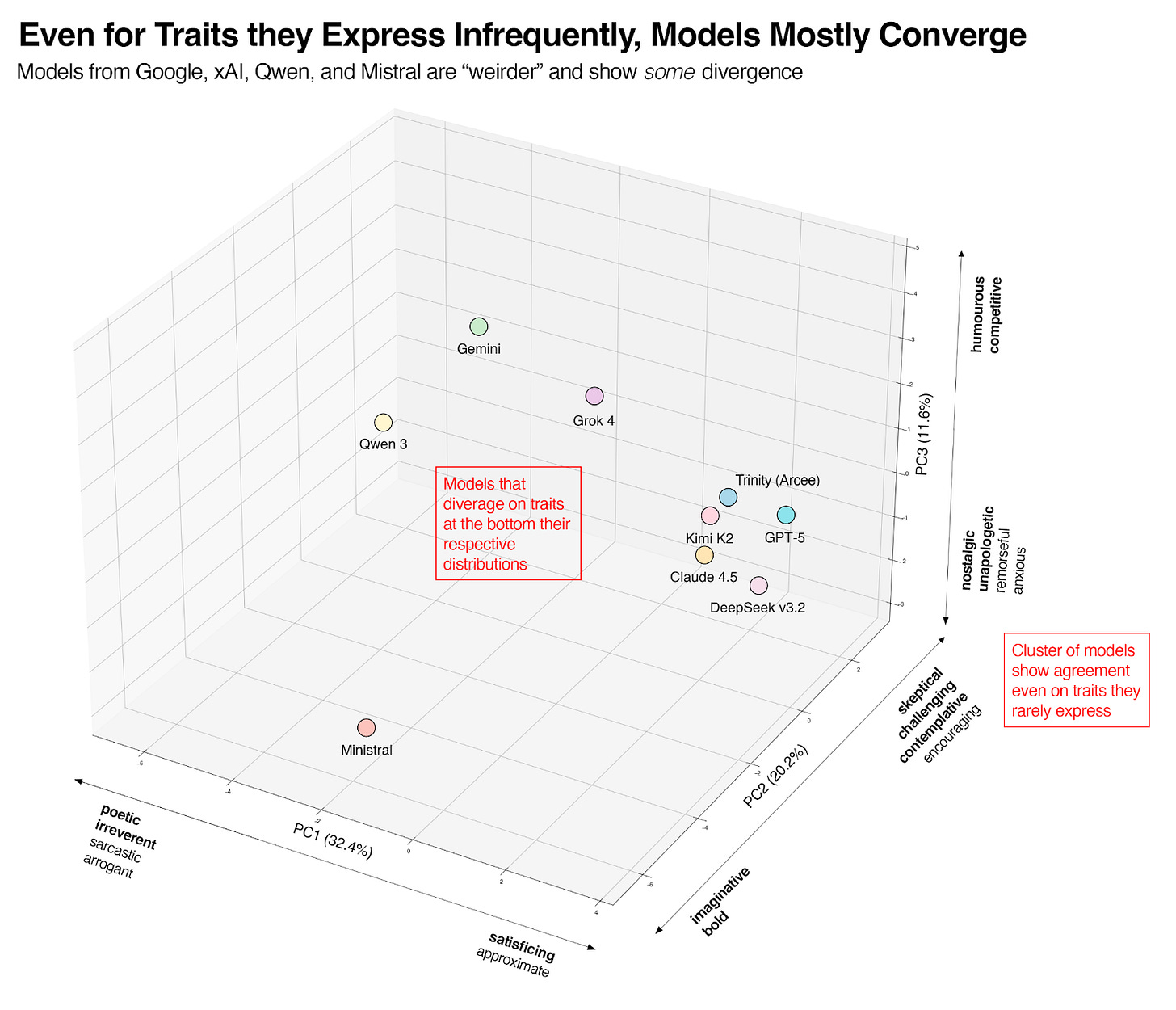

The variance that does exist tends not to come from the most expressive traits, but rather comes from disagreements around what models dislike. A principal component analysis we did, shown in Figure 5, identified which traits accounted for most of the variance between models and helped us get a holistic view of which models were “weirder” than others. Again, all models are very similar, but for some clusters of traits, models from Google, Qwen, xAI, and Mistral were somewhat different from others.

Figure 5: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) that shows which clusters of traits account for the most variance. Variance among models mostly comes from traits they rarely express, which is why none of the Top 20 highest-ELO traits (Figure 2) appear in this graph. Percentages for each axis (e.g., 32.4% for the x-axis) show the importance of each trait cluster. Models that stray from the norm tend to be more creative and are, for example, more expressively poetic and humorous.

The models from Google (Gemini) and Alibaba (Qwen) were particularly interesting. We found them to be more pessimistic and critical (and more emotionally volatile) than other models. Speculatively, this could mean their models are better aligned against sycophancy than their peers. Ultimately, differentiation in the chat space is hard to come by, and our results suggest that the teams behind Qwen and Gemini prefer their “helpful” assistants to be those unafraid to push back.

Ablations

Given budget constraints, we did minimal ablation testing. However, the relatively inexpensive nature of GLM 4.5 Air, our judge model, enabled us to perform one ablation, in which we modified its temperature from 0.1 (closer to deterministic) to 0.7, making it more stochastic and generally unsuitable for classification tasks like the one we ran. Despite this, our results remained almost exactly the same. The Spearman correlation for judgments between both instances of GLM 4.5 Air was >97%, including for more idiosyncratic models Gemini 3 and Qwen 3.

LLMs can be measured on all kinds of axes, from their quantitative performance on math and coding to their truthfulness or even on their propensity to misdirect. However, given the relative obscurity of character training, there have been few studies focused solely on the character of AI models, even as users increasingly emphasize personality when selecting how and when to interact with certain models. In this experiment, we leverage the revealed preference method formulated by Maiya et al. in Open Character Training and show that most model providers have converged on a personality that is uncontroversial and straight-to-the-point, often at the expense of more creative expression. Nevertheless, at lower ends of the distribution, e.g., traits that models try to avoid, there is more disagreement. Some models are funnier and more sarcastic, while others stick to a very straightforward approach. Ultimately, model providers are under the constant push and pull of trying to reduce the over-flattering nature of their models while maintaining their helpfulness, an objective our results show they continue to struggle with. Future research that builds on our work could involve linear probes to more robustly verify various forms of trait expression in open models.

Shahaf David, Yair Meidan, Ido Hersko, Daniel Varnovitzky, Dudu Mimran, Yuval Elovici, and Asaf Shabtai. ProfiLLM: An LLM-Based Framework for Implicit Profiling of Chatbot Users. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.13980, 2025.

Hasibur Rahman and Smit Desai. Vibe Check: Understanding the Effects of LLM-Based Conversational Agents' Personality and Alignment on User Perceptions in Goal-Oriented Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.09870, 2025.

Sharan Maiya, Henning Bartsch, Nathan Lambert, and Evan Hubinger. Open Character Training: Shaping the Persona of AI Assistants through Constitutional AI. arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.01689, 2025.

Pengrui Han, Jonathan C. Booker, Michael J. Ryan, and others. The Personality Illusion: Revealing Dissociation Between Self-Reports & Behavior in LLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.03730, 2025.

Huiqi Zou, Pengda Wang, Zihan Yan, Tianjun Sun, and Ziang Xiao. Can LLM “Self-report”?: Evaluating the Validity of Self-report Scales in Measuring Personality Design in LLM-based Chatbots. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.00207, 2024.

GLM-4.5 Team, Aohan Zeng, and others. GLM-4.5: Agentic, Reasoning, and Coding (ARC) Foundation Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.06471, 2025.

Prime Intellect Team, Mika Senghaas, Fares Obeid, Sami Jaghouar, William Brown, and others. INTELLECT-3: Technical Report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2512.16144, 2025.

Wenting Zhao, Xiang Ren, Jack Hessel, Claire Cardie, Yejin Choi, and Yuntian Deng. WildChat: 1M ChatGPT Interaction Logs in the Wild. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.01470, 2024.

Zhaofeng Wu, Xinyan Velocity Yu, Dani Yogatama, Jiasen Lu, and Yoon Kim. The Semantic Hub Hypothesis: Language Models Share Semantic Representations Across Languages and Modalities. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.04986, 2024.

Elliot Kim, Avi Garg, Kenny Peng, and Nikhil Garg. Correlated Errors in Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.07962, 2025.

Koki Wataoka, Tsubasa Takahashi, and Ryokan Ri. Self-Preference Bias in LLM-as-a-Judge. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.21819, 2024.

Horace He and Thinking Machines Lab. Defeating Nondeterminism in LLM Inference. Thinking Machines Lab: Connectionism, Sep 2025. https://thinkingmachines.ai/blog/defeating-nondeterminism-in-llm-inference/

Chenghao Yang and Ari Holtzman. LLM Probability Concentration: How Alignment Shrinks the Generative Horizon. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.17871, 2025.

Mrinank Sharma, Meg Tong, Tomasz Korbak, David Duvenaud, Amanda Askell, Samuel R. Bowman, Newton Cheng, Esin Durmus, Zac Hatfield-Dodds, Scott R. Johnston, Shauna Kravec, Timothy Maxwell, Sam McCandlish, Kamal Ndousse, Oliver Rausch, Nicholas Schiefer, Da Yan, Miranda Zhang, and Ethan Perez. Towards Understanding Sycophancy in Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.13548, 2023.