The Permanent Underclass

Lessons from China on how to escape

Assuming we enter a post-labor scarcity world, where all economically valuable goods can be produced with ~no human labor, it reasonably follows that existing class hierarchies will calcify. Why is this default outcome? Well, right now, more capital (e.g., money, AIs, datacenters, companies with these things) doesn’t strictly buy more results, as evidenced by the existence of startup ecosystems whose central thesis are that talent can sometimes outcompete capital. But in the future, the link between capital and results will become inextricable since the cost of AI labor will significantly cheaper and more scalable than its human counterpart.

And so, given that labor-derived economic outcomes—currently the largest enabler of class graduation—will evaporate, class hierarchies will remain static post-AGI.1

So! You find yourself in the permanent underclass because you did not enter this point in time with a sufficient enough capital base to separate yourself from the rest of humanity who is similarly unable to generate leverage from their labor alone.

What’s left?

For one, you are either out of a job or soon to be out of a job. The doomers almost certainly get this one right. If capital can do your job more effectively, then why would you be paid a supracompetitive price to do the same job, worse?

With that said, it’s logical to assume some sort of government, company, or private individual-provided income disbursement will materialize. It’s possible that there will be less incentive for the ‘elite class’ to care about the underclass, but a sufficiently aligned AI and the fact that the U.S. is a liberal democracy probably mean some sort of income disbursement will happen.

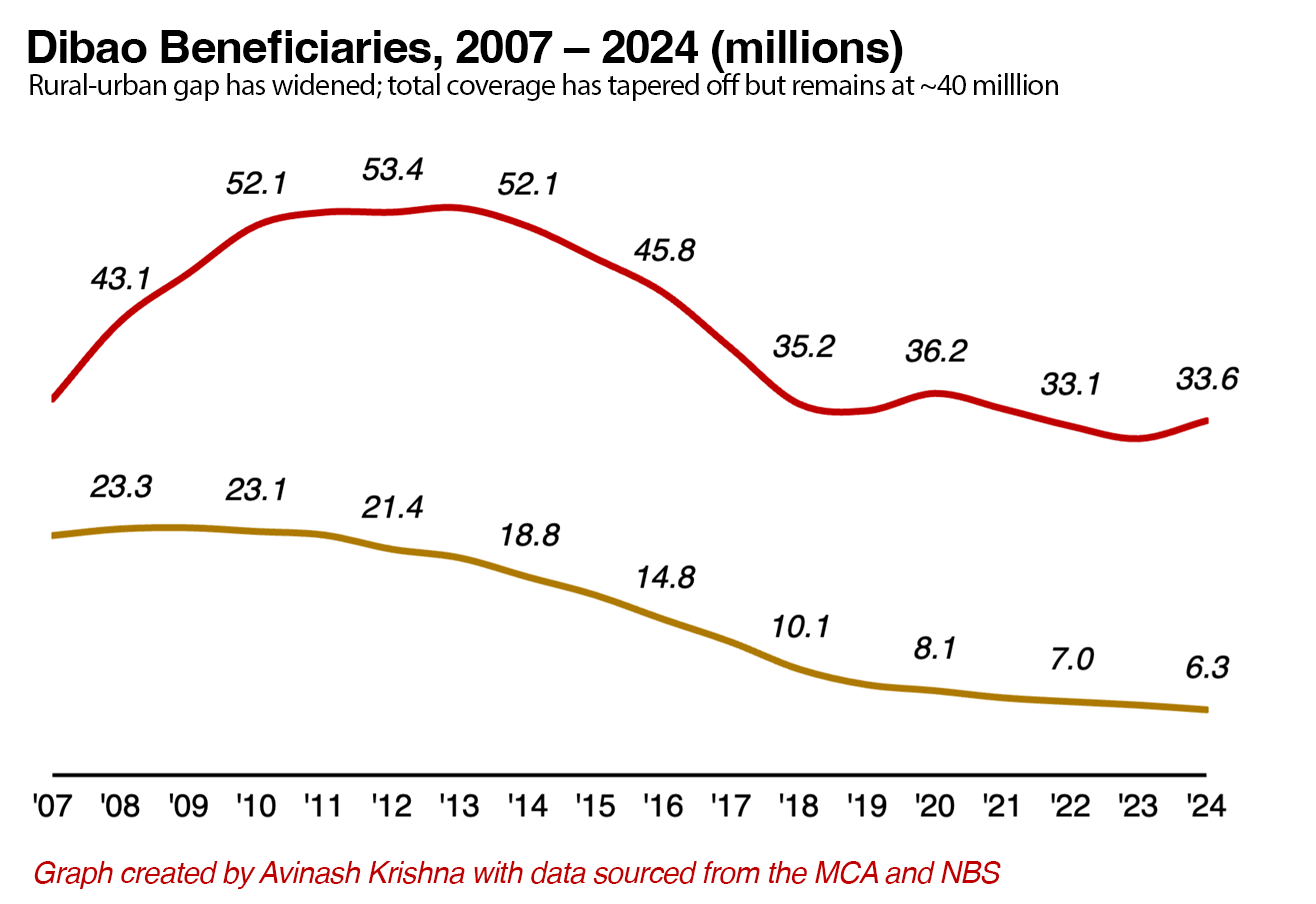

China, via the dibao system, is a decent example of what a large scale, unconditional cash transfer system could look like. By 2015, China had effectively eliminated rural poverty2 through various means alongside fairly broad implementations of the dibao system, with coverage peaking at 75 million people!! in 2011 and slowly tapering off since then (China has gotten a lot wealthier since).

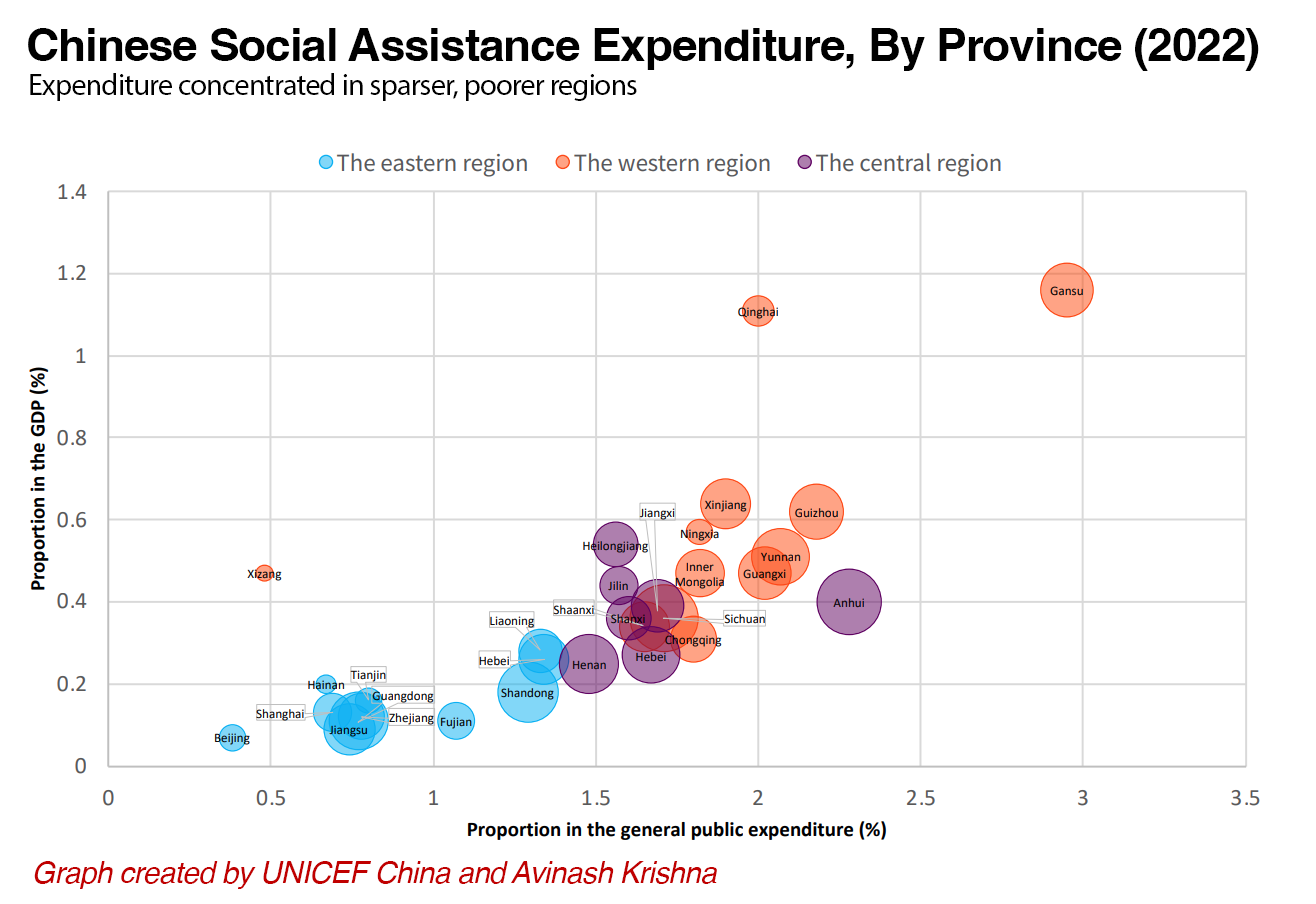

This makes sense. Rural areas are significantly poorer than their urban counterparts and therefore have the largest number of participants3, meaning that the bulk of expenditure is dedicated toward them4. Hold that thought.

China also has something called the hukou system, which ages back to the pre-dynastic era, and classifies people as rural or urban,5 initially to stave off the dual threat of potentially destabilizing, mass urban migration and potential urban uprisings against the current regime. From Dan Wang in Breakneck on how hukou is used nowadays:

Many people still live under the strictures of the hukou, or household registration, an aim of which is to prevent rural folks from establishing themselves in cities by restricting education and health care benefits to their hometown. Controls are far worse for ethnoreligious minorities: Tibetans are totally prohibited from worshipping the Dalai Lama, and perhaps over a million Uighurs have spent time in detention camps that attempt to inculcate Chinese values into their Muslim faith.

If you are at all familiar with Foxconn’s labor practices, this should ring a bell. If you aren’t, in short, China’s economy relies heavily on internal migrant labor to staff factories where churn rates can be upwards of 300% per year, so there needs to be a nearly endless supply of migrants. The state provides these migrants with little social support in urban areas, and does not let children or parents of migrant workers come with them (look up “left-behind children”). This means that if you are part of a certain group of people, your entire bloodline gets exploited for its labor, captures very little of the value it creates, and can’t what it does capture to benefit family members back home. In effect, China has a system where it 1. systematically excludes people from high-value economic participation and 2. directs subsistence amounts of cash transfer aid toward. This can be approximated to a UBI for the permanent underclass. By the way in this analogy, hukou ≈ structural barriers to entering the AI–capital-owning elite class and dibao ≈ UBI.

This isn’t great per se, but for future members of the permanent underclass, it should inspire some confidence that their situation is quite precedented. So, what to do?

In China, you do not climb out of the rural hukou bucket by working harder, you do it by getting reclassified in the eyes of the state. Guanxi—family and political ties—are for most the main way out: the scarce, urban, non-factory jobs are generally reserved for residents (not migrants), but guanxi provides a path for rural kids who have been slotted into their parents’ networks. Nepotism is nothing new to the Western world, but the extent to which guanxi is treated as foundational to the social and even political system is staggering.

Formal Party status is a second way: Communist Party members earn roughly 10-25% more than comparable non-members, with the advantage of course largest at the top of the distribution6. These badges are rationed and young people increasingly treat admission as their main route to stable livelihoods. And even at the bottom, local village and township cadres decide who actually receives dibao and related assistance: “eligibility” is almost exclusively filtered through political and moral criteria since there isn’t enough money to go around.

In other words, in a very large, real-world, quasi-underclass, the escape routes are already explicitly social and political status games. This will be even more true post-labor scarcity, given there will be no way to differentiate via material goods, meaning the only way out will be to play these games so as to accumulate the last scarce resource. There will be no capital nor guns, and no Marxian proletarian revolution.

Part of the new social hierarchy, human-to-human interaction, will be familiar, but the other part, human-to-AI interaction, will result in an entirely new structure that includes non-sentient entities. It’s not a huge leap to imagine a Her-style acceptance of AIs into traditional human relationships, and considering that intelligence, especially smaller models, will be effectively free, their integration should be seamless. Who knows, maybe there will be some sort of mass upload of human minds onto digital substrates. Frankly, it’s not super clear.

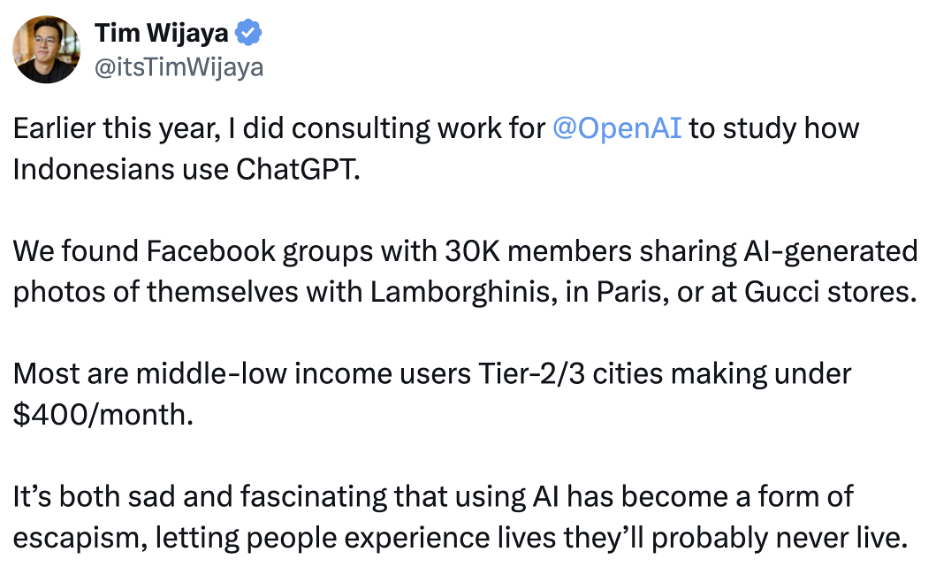

Regardless, we can already see the inklings of novel, AI-enabled interactions with Sora-style feeds and the general enslopification7 of the internet, meaning that people—and especially poorer people who are more susceptible—are interacting with this content daily. Most Americans don’t grasp the frequency with which they are using AI8, and regardless are generally open to the idea of AI assisting with day-to-day activities9.

Moreover, AI is already piercing social interactions in more obvious ways. Browse Facebook for even 10 minutes and you will see similar online interactions to what Tim describes here:

Ultimately, it seems, this part of the social shift will happen not with a bang, but with a whimper.

Now unfortunately, along with the issue of the utter lack of resources underclassmembers will possess, their social positioning relative to the elite class will create problems. Yes, it’s true that the underclass will probably live in close proximity to and share the same ethnic, religious, and educational background as the elite class. But this just makes the underclass archetypical “outgroup” members, which in the Scott Alexander conception, is

Proximity plus small differences. If you want to know who someone in former Yugoslavia hates, don’t look at the Indonesians or the Zulus or the Tibetans or anyone else distant and exotic. Find the Yugoslavian ethnicity that lives closely intermingled with them and is most conspicuously similar to them, and chances are you’ll find the one who they have eight hundred years of seething hatred toward.

This means that the lack of social mobility, despite being similar in every other way, places the underclass in the outgroup. So along with the structural economic barriers to class graduation, there will be an immense ‘othering’ barrier to overcome.

Therefore, there are two high-leverage things any person can do right now.

You can either, as the meme that inspired this post suggests, accumulate as much capital as you can, now. The advice of ‘hustle in your 20s, enjoy later’ is hyper-relevant in the scarcity age.

The other, similarly nebulous option, is becoming incredibly good at social games. This is the skill of navigating institutions and cliques, and of competing on the axis of social signaling, not raw competence.

References

By default, capital will matter more than ever after AGI. (beren, 2025).

Do Government Transfers Reduce Poverty in China? Micro Evidence from Five Regions. (OECD, 2017). Findings around the elimination of rural poverty are contested, but it’s indisputable that China has orchestrated an incredibly successful increase in wealth for the poorest fringe of its society, at a never-before-seen scale.

UNICEF China, Budget Brief: Social Assistance in China. (UNICEF China, 2024).

This graph has a strong correlation to Chinese population density by region (and by proxy, GDP per capita), making it clear that most dibao funds are more directed toward poorer regions.

China has made incremental hukou reforms since 1980 and recently eliminated the mandatory agricultural/non-agricultural split. This has not had much of an effect and given the comparatively limited resources more rural regions of China have, hukou can still be likened to a form of caste system.

Guanxi Networks and Job Mobility in China and Singapore. (The University of North Carolina Press, 1997).

Enslopification. (Avinash Krishna, 2025).

A majority of Americans say they interact with AI at least several times a week. (Pew Research, 2025). The title is somewhat misleading: ~every American interacts with AI multiple times a day, even through Google search, they just don’t realize it.

Most Americans would let AI assist with day-to-day tasks and activities. (Pew Research, 2025).

Brilliant framework mapping China's hukou system to future class stratification. The hukou-dibao parallel is especially insightful because it shows how even functional systems of redistribution can coexist with rigid class barriers. What strikes me though is that China's system was explicitly designed top-down to manage internal migration, whereas post-AGI stratification might emerge more organically from capital accumulation patterns. The key difference is intentionality. In China, the state actively prevents mobility through policy; in a post-labor world, the barriers might be more subtle but equally insurmountable becausecapital compounds in ways human networks can't replicate at scale. Your point about social games mattering more resonates, but I wonder if we're underestimating how quickly AI mediates those games too.

Love this!